It is appealing to think of oneself as powerful. Modern mass media often focuses on the concept of freedom for individuals. Modernist movies such as Braveheart and The Patriot touch on the concept of free choice and what one person can accomplish if they try. Movies such as The Matrix appear to give postmodernist interpretations of individual freedom, as if it were a frivolous pursuit. Common assumptions about freedom, in society, include its necessity for individuals to live a full life, and presume the existence of choice as a driving and determining factor in the development of technology. Postmodernists are skeptical of the concept of free choice and reduce human individuality to a crisis, or struggle, of resistance against domination.

The idea of postmodernism is credited to the work of Frederic Jameson in the field of architecture. Notably, “Jameson’s…efforts rest on the most comprehensive grasp of Marxism among living American critics,” [1]. Postmodernism was popularized in America through the work of Stuart Hall, who wrote of individuals as a “fragmented, decentered agent,” and of “paradoxes which are eternal (and hence insoluble).” He claimed that there is “nothing left but competing desires,” and posited that a solution is “the removal of scarcity through the rational deployment of global resources,” [2]. Bruno Latour, in 1987, appears to have defined technoscience in a postmodern light, saying it “has the characteristics of a network…resources concentrated in a few places” and that “the construction of the centres requires elements to be brought in from far away- to allow centres to dominate at a distance,” [3]. Andrew Feenberg’s Democratic Rationalization appealed to reason for a change in culture and politics that would solve the alleged crisis of late capitalism. He argued that “at least in the ex-Soviet Union everyone could agree on the need for authoritarian industrial management,” and that “insofar as modern societies depend on technology, they require authoritarian hierarchy.” He revealed that in “Heidegger’s formulation…and Ellul’s theory…we have become little more than objects of technique, incorporated into the mechanisms we have created.” As Marshall McLuhan once put it, technology has reduced us to the “sex organs of machines,” [4]. Karam Adibifar’s Technology and Alienation in Modern-Day Societies depicts “the “social cost” of “mass alienation,” which has already weakened our “collective conscious,” and has become an “opiate of the masses and a source of disintegration, deviance, strain, and divisiveness.” He argues that “if the progress of technology continues at the current pace, we are likely to witness more class conflict, war, environmental degradation, poverty, and more internal and external alienation,” [5]. In Arundhati Roy’s The End of Imagination, India’s development of the nuclear bomb in the 1990’s was called “fascism on the breeze.” Roy depicts the bomb as a declaration of “war on their own people- us,” and protests “against having a nuclear bomb implanted in my brain.” Roy declares that “India is an artificial state- a state that was created by a government, not a people…created from the top down, not the bottom up,” and that “India’s nuclear bomb is a final act of betrayal by a ruling class that has failed its people…is the most antidemocratic, antinational, antihuman, outright evil thing that man has ever made,” [6].

“We’re left with no arms, in this power struggle.”

-Band, System Of A Down (Source: LyricFind)

These critics of modernism have strong points about the err of whiggish historiography and the centralization of power. They appear correct in claiming that many groups have become permanently dominated by existing power structures. As non-dominant members of society we are at times denied a space/place for resistance or for pushing back against domination. However, these critics appear to be misdiagnosing the problem and its contributing causal factors, as well as employing a rushed prognosis and solution.

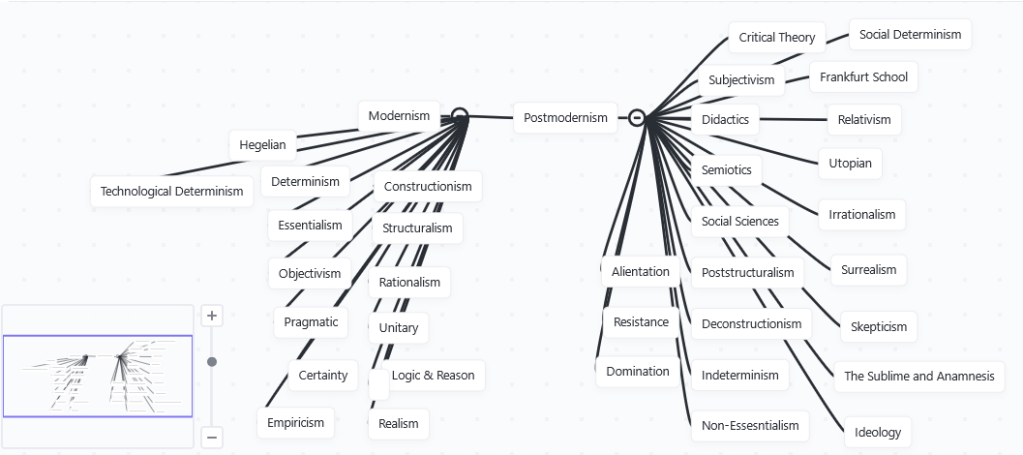

These proponents of postmodernism are vague in their assertions, but appear to suggest that a collective consciousness exists, as depicted in various collective identities, and that such collectives should use social resistance to existing power structures to overhaul political systems in order to impose a collective social identity on the development of technology. Critic of postmodernism, James Trilling, asserts that “postmodernism is committed to erasing the heritage of western white male dominance on every level of thought and action,” and that it is “neither of the left nor the right” but “a separate force, hostile to both conservative and liberal ideals.” He defines a modernized society as “one that uses inanimate sources of energy to such an extent that even a relatively slight reduction from these sources could not be made up by switching back to animate sources,” [7].

Postmodernism does appear to have been used as an attack on western power structures through misrepresentation and reduction of the self and reality. A real solution to the problems of modernism may be to conceive of technology (or use of technology) capable of empowering an individual with inanimate sources of energy such that neither the state nor any group can stop the individual from using it. While peaceful nuclear technology could achieve such a feat, it is no wonder that dominant, eastern and western, imperialist nation-states have regulated such technology out of reach for individuals (while weaponizing it for their own purposes of domination). The solution to such dilemmas, then, might be in the erasure of domination through the abolition of the modern, and the post-modern, nation-states.

SOURCES

- Bové, Paul A.. Early Postmodernism: Foundational Essays. United Kingdom, Duke University Press, 1995. Link, https://www.google.com/books/edition/Early_Postmodernism/OiowPzKwscwC?hl=en&gbpv=0

- Stuart Hall: Critical Dialogues in Cultural Studies. United Kingdom, Taylor & Francis, 2006. Link, https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=ISuIAgAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA151&dq=postmodern+history&ots=Og3Nuwdk-Y&sig=26ZWG1Sw3X4p1Lu0OuCeWkbx8iY#v=onepage&q=postmodern%20history&f=false

- Latour Bruno. Science in Action: How to Follow Scientists and Engineers through Society. Open University Press, 1987.

- Feenberg, Andrew. “Democratic Rationalization”. Readings in the Philosophy of Technology. David M. Kaplan. Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield, 2004. 209-225

- Adibifar, Karam. “Technology and Alienation in Modern-Day Societies.” International Journal of Social Science Studies, vol. 4, no. 9, September 2016, pp. 61-68. HeinOnline.

- Roy, Arundhati. The End of Imagination. The Cost of Living, 1999, pp.91-127. New Jersey Institute of Technology.

- Trilling, James. “A Modernist’s Critique of Postmodernism.” International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society, vol. 9, no. 3, 1996, pp. 353–71. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/20019842.